Actualités

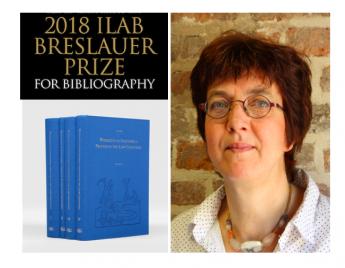

Interview with Dr. Ina Kok, Winner of the 2018 ILAB Breslauer Prize for Bibliography

1. On behalf of ILAB and the rare book trade community, our heartfelt congratulations on winning the 17th ILAB Breslauer Prize. Your book was chosen out of over 50 submissions for this year’s prize.

What brought you to this subject and to the field of incunabula research?

Thank you very much for your congratulations! I feel very honored with this great award! I did not know beforehand that my book was submitted, so the news came to me totally unexpected and also exactly on my last birthday!

You ask me what me brought to the subject of this book: the woodcuts in the incunabula from the Low Countries. Well, this book originated in its origin from my doctoral thesis (1978) for my study Dutch Language and Literature at the University of Amsterdam (main direction: Historical Literature). The subject was: the woodcuts of the prominent fifteenth century printer Gerard Leeu who was working in Gouda and later in Antwerp. During my studies I had been an assistant of Prof. Herman Pleij for a year and I was involved in his Late Medieval folk and trivial literature project. He asked me among other things to develop a search system for the many fifteenth and sixteenth century woodcuts in his archive of photocopies. Actually, the very first source of my book is here! It must have been around 1976.

Later I followed the postgraduate study Book and Library Science at the same university. In this study the lectures Book History of Prof. H.D.L. Vervliet and Graphical Techniques of the late Prof. G.W. Ovink inspired me to undertake the plan for a dissertation on the entire corpus of fifteenth-century book woodcuts from the Low Countries.

I applied for a three-year grant from the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO). I already knew then that three years would be far too short for the entire research, but I thought that if I were modest, I would have more chance of winning. And it worked: I received the subsidy and could start in November 1979. For this dissertation Vervliet became my supervisor and Prof. R.W. Scheller (Art History, Amsterdam) my co-supervisor.

Of course the work lasted much longer than those three years, especially after I got a part-time job as a curator in the City and Athenaeum Library of Deventer in 1985 and I had to carry out my research next to that job. In the end I took my doctoral degree in 1994.

2. The book is published in four volumes and shows nearly 4000 examined woodcuts. How many years have you been working on this subject and when did you start working with the publishing house Brill on the actual publication?

Yes, with the repetitions of those 4000 woodcuts included, in later editions of the same book, but also in very different books, it were 12,000 prints of the blocks! It was indeed a very extensive research, all the more since I also studied the wear and tear of the woodcuts to derive evidence for new dating of the books.

My dissertation was self-published, in a simple layout and unillustrated, though I intended to bring out a fully illustrated commercial edition not long afterwards. But partly because we had two children shortly thereafter, this term was longer than expected...

Yet the project was only temporarily shelved.

I am very happy that Hes & De Graaf Publishers, now been taken over by Brill, have been willing to undertake the vast and time-consuming project to publish the work. As early as 2002, plans for an edition were on the table, though there were still many hurdles to overcome and decisions to be made afterwards. As of 2010, however, the publication of this reference work was constantly on the agenda of my publisher.

When Cis van Heertum, a former curator of the Bibliotheca Philosophica Hermetica in Amsterdam and now an independent translator, was engaged to translate this voluminous and elaborate work, a successful end to the project came in sight. Eventually the book was published in mid-2013.

In answer to the first part of your question: at that time I was busy with woodcuts in incunabula from 1979 onwards, so 34 years.

3. You credit a vast number of institutions who have contributed to the book, where are the majority of the collections based today?

The inventory in my book is based on the complete corpus of the 2229 Dutch incunabula that have been identified to date.

All libraries relevant to the present study were visited to check the Dutch incunabula in the collections for the presence of woodcuts and to order reproductions. Naturally the first place of call was the Koninklijke Bibliotheek in The Hague, which holds the largest collection of Dutch incunabula.

Similar research visits were made to the University Library Amsterdam, the Bibliothèque Royale Albert Ier in Brussels, the British Library in London, the University Library in Cambridge, the Bodleian Library in Oxford, the Staatsbibliothek in Berlin and the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris.

The net was cast wider to include other university libraries as well as city libraries with rare books holdings in the Netherlands and abroad. Countless libraries, at home and abroad, were approached with requests for information and reproductions in the process.

4. You are currently working on a new publication, due to be published in 2020. Would you give us a little preview of what it entails?

Yes, I am currently working on an annotated edition of the correspondence between William Martin Conway (1856-1937) and Henry Bradshaw (1831-1886).

The English art historian Conway is my distant predecessor: he was the first to offer a survey of the woodcuts appearing in the incunabula of the Low Countries, namely The Woodcutters of the Netherlands in the Fifteenth Century, from 1884. This was the first attempt at a comprehensive study of the incunabula woodcuts of a particular geographical area. But unlike my book, which is bibliographic in nature, Conway's approach was art-historical.

Conway, the son of a canon of Westminster Abbey in London, went up to Cambridge to read mathematics and theology, but soon developed an interest in art history, and acquired a knowledge of the field which was largely self-taught. He began studying the early German and Flemish engravings in the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge in 1879. After studying the engravings, he made a natural switch, as it were, to the woodcuts of the same period. As these were mostly to be found in early printed books, he called in the help of Bradshaw, librarian of Cambridge University Library and a renowned philologist and bibliographer. At the time, Bradshaw was virtually the only one to take an interest in incunable woodcuts. After having examined the incunabula at Cambridge, young Conway was encouraged by Bradshaw to travel to the continent to expand his research. For a year he toured Western Europe, visiting libraries and private collections in search of woodcuts in incunabula that had been printed in present-day The Netherlands and Belgium.

During this voyage of investigation Conway corresponded in detail with his teacher about the collections he visited, the incunabula of the Low Countries and especially the woodcuts he discovered. Sometimes even valuable data have been given about single copies which are lost now and we get a good image of the organisation of the academic libraries anno 1880.

The correspondence, that is kept in the University Library in Cambridge, consists of 120 letters, 51 from Bradshaw an 69 from Conway. For comparison the Bradshaw-Holtrop-Campbell correspondence, which was published in 1966 by Wytze and Lotte Hellinga, consists of 101 letters, of which 48 from Bradshaw.

Besides in the Conway-Bradshaw correspondence we get a good insight in the person of Bradshaw, even more than in the Bradshaw-Holtrop-Campbell correspondence because his relationship with his pupil was on the whole informal, hearty and paternal.

All in all the publication of this correspondence will be invaluable for the history of the bibliography of early printing in the Netherlands. In addition owing to the many personal details the letters contribute to our hitherto little knowledge of the renowned Bradshaw the incunablist.

5. You are based in Amsterdam where the next ILAB congress will be held in 2020. Many ILAB booksellers will take part in this much-anticipated event. What should any bibliophile or scholar, visiting this unique city, not miss?

It is fun to browse the Amsterdam Book Market that is held every Friday from 10 am till 6 pm on the Spui. The Spui is a small square in front of the well-known Beguinage, so it is a very pittoresque environment there. For over 20 years this book market attracts booklovers from the Netherlands as well as from abroad. They all know: this is the place to look for that one book still missing. The whole year around some 25 booksellers from all over the Netherlands bring their old, rare, second hand and out-of-print books to this market, which is to be found in the very heart of old Amsterdam. A stiff breeze or rainy weather is no reason to stop the market!

Furthermore, there are a number of beautiful libraries in the center of Amsterdam that you can visit:

To begin with, the library of the Rijksmuseum, the Cuypers Library. This is the largest and oldest art historical library in the Netherlands. Following an intensive restoration campaign, it has now been fully returned to its former glory. In the newly reopened museum, the visiting public is now able to admire the nineteenth-century library’s splendid reading room!

As everyone knows, Amsterdam has a famous zoo: Artis. Less known is the

Artis Library: a nineteenth-century gallery library located at Plantage Middenlaan 45. The name is used for both the building and the library collection that is placed there. The Artis Library is part of the Special Collections of the University of Amsterdam. You can visit the Special Collections too at: Oude Turfmarkt 129.

Ets Haim is the oldest functioning Jewish library in the world. It was established in 1616 as part of the Talmud Torah school, and has occupied its current premises in the marvelous complex of the Portuguese Jewish Synagogue in Amsterdam since 1675. The address is Mr. Visserplein 3. The library, which consists of some 560 manuscripts and 30.000 printed works, possesses a large, rich collection relating to Jewish life in the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, and as such it has been a core part of Amsterdam’s cultural heritage for almost 400 years.

To visit this library, groups must request a tour. During the tour, the first Sephardic Jews in Amsterdam, the education system that they developed and the role that Ets Haim fulfilled in them are discussed. The history and realization of the collection of books and manuscripts is discussed in detail. Some top pieces are also shown.